felix86 25.05

A lot of progress was made during the month of April!

Before we dive in, I want to thank the donors on Ko-Fi who helped me raise funds for hardware and games. In particular, I’d like to thank Sonicadvance1 from FEX-Emu for his significant $1000 donation! Thanks so much!

The GPU trials

Using a proper GPU with a RISC-V board is… tricky currently.

Initially I tried an NVIDIA GTX 1050 Ti, but I quickly realized that Bianbu lacks nouveau driver support. Next, an AMD Radeon HD 7790 was tried, however that brought up errors during initialization. Finally, I picked up an AMD HD 7350, as the Bianbu wiki claimed it was supported – and thankfully, it was.

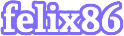

The BPI-F3 has no PCIe slot, the mPCIe had to be used with an adapter

The BPI-F3 has no PCIe slot, the mPCIe had to be used with an adapter

Being able to use a GPU has been very helpful. All games prior to this point were running with llvmpipe, which is a software GPU fallback that draws graphics using your CPU. This is extremely expensive, and exponentially so for any game that does anything other than copy a framebuffer to the screen. Some games managed to cope, like VVVVVV at “decent” framerates, while others like World of Goo would run at a staggering 0.5 frames per second. Other games like SuperTuxKart would freeze during the compilation of certain shaders, which would happen both on actual x86-64 hardware and under felix86. Having a GPU present allowed SuperTuxKart to get us into a race at 10 frames per second, which we hope to raise in the future!

We can finally race!

We can finally race!

Getting a GPU to work provided a great performance boost in most games. Some games, though, were very stubborn to continue running slowly. In the next section you’ll find out why!

Self-modifying code

During April, initial support for self-modifying code was added.

Self-modifying code can take many forms:

- A library being loaded at an address, unloaded, and a different library being loaded at the same address

- A recompiler making modifications to its own code for performance, such as block linking

- Anti-emulator/anti-debugger tactics for DRM or anti-cheat

The reason self-modifying code is a problem is because recompilers compile chunks of code at a time (called basic blocks) and cache them to prevent future recompilations. This caching happens based on the address. If there’s self-modifying code however, the underlying guest code has changed but the cached host code is still the same. In those scenarios, we need to mark those blocks as invalid and recompile them. This is the basic idea, there’s other techniques that deal with other types of self-modifying code for better performance.

Without self-modifying code support, Celeste would run, but very, very slowly. The loading times were the worst part, the game took around 100 seconds just to load the graphics, getting to the menu could take up to 10 minutes or more. The menu would render at less than 2 FPS, with or without a GPU.

With self-modifying code support, these loading times were vastly reduced and the game could run at around 20 FPS with some stutter when loading new areas. This is a massive boost in performance and was quite unprecedented!

The reason here is that Celeste is a game written in C#. This game runs under a C# runtime environment with a JIT that translates CIL to host machine code. This environment, called Mono, has a lot of self-modifying code where the originally slow recompiled code gets gradually optimized to perform faster. Now, if there’s no self-modifying code support, these optimizations never get realized by our emulator, as it keeps running the cached code without realizing the guest code has changed, thus performing a lot worse.

Not all types of self-modifying code are supported yet, but library loading/unloading (via the use of munmap and mmap) is supported, and the same goes for self-modifying code on blocks other than the currently executing one. There’s a nasty possible case of self-modifying code where instructions within the block itself are modified, but this is maliciously done by anti-cheat or DRM software, and we are not at that point yet.

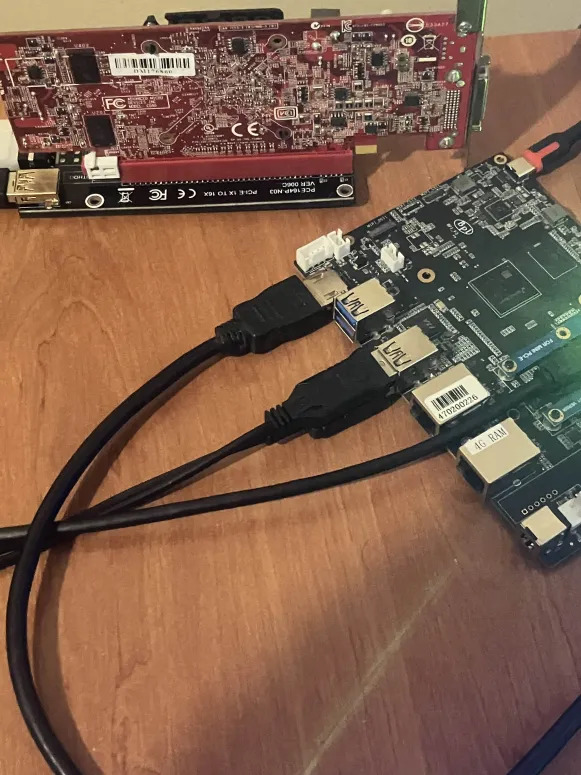

After fixing a couple more bugs, Celeste now gets in game, and at ~20 FPS!

After fixing a couple more bugs, Celeste now gets in game, and at ~20 FPS!

Implementation details

Detecting self-modifying code happens by disallowing write access to pages that contain guest code that we recompiled. A signal handler will then be triggered on writes to these pages and we can invalidate the blocks in those pages by using a map to find all blocks contained within them for all the threads.

We have an “invalidate the caller” thunk function. We replace the first two instructions of each invalidated block with a jump to that thunk function. The jump is special:

void Recompiler::invalidateBlock(BlockMetadata* block) {

u64* address = (u64*)block->address;

const u64 offset = (u64)invalidate_caller_thunk - (u64)address;

const auto hi20 = static_cast<int32_t>(((static_cast<uint32_t>(offset) + 0x800) >> 12) & 0xFFFFF);

const auto lo12 = static_cast<int32_t>(offset << 20) >> 20;

u64 storage;

Assembler tas((u8*)&storage, 8);

ASSERT(isScratch(t4));

ASSERT(isScratch(t6));

tas.AUIPC(t4, hi20);

tas.JALR(t6, lo12, t4);

__atomic_store(address, &storage, __ATOMIC_SEQ_CST);

}

As you can see, the jump also links to t6. This is an available scratch register that we specifically use in our thunk function

to get the BlockMetadata struct when something jumps to this invalidated block.

It’s also important to note that block links look like this:

as.AUIPC(t4, hi20);

as.JALR(t5, lo12, t4);

So the registers t5 and t6 are used to pass info to the invalidate_caller_thunk. The t5 register holds the caller that needs to be

unlinked (and later relinked to the new block), while t6 holds the address of the invalidated block. Actually it holds the address + 8 of the invalidated block, and t5 holds the address + 8 of the link location. But we can do a simple subtraction.

Afterwards, invalidate_caller_thunk is going to save the context and jump to a C++ function that finds the block, marks it as invalid, and unlinks the caller, and marks the area for linking when the compilation happens. It will then jump back to the dispatcher. The dispatcher will compile the now invalidated block and the relinking will naturally happen again.

Context saving rework

The x86-64 registers are statically allocated to RISC-V registers. When entering the recompiled code we load them from memory, when we exit we store them in memory.

Previously, this would happen at the basic block level. When a basic block is entered, the registers used in that basic block will be loaded from memory as they are needed, and at the end of the block we write everything to memory. However this approach brings up a couple problems:

- When multiple blocks are linked together, there’s multiple loads/stores that could’ve been otherwise avoided

- When a signal happens, we don’t know which registers are loaded with a correct value (which represents an x86-64 register), or with garbage

The first problem is more of an assumption. One could assume that this would be expensive, however the alternative, which is loading/storing them in the dispatcher, could also be a performance bottleneck in scenarios where the dispatcher is hit often.

The second problem is worse. To handle that issue in the past, we used to walk through the instructions from the start of the block until the PC at the time of the signal and decode the instructions. Any instructions modifying a statically allocated register would mean the register has an updated value that is not yet reflected in memory, and we need to pull it out of the ucontext_t struct.

However, if we load all the registers in the dispatcher, and ensure whenever recompiled code is executed that the statically allocated registers hold correct values, we can simply pull the values from ucontext_t at all times and the values will not be garbage!

This is what this pull request achieves.

Another issue with our former approach is that walking instructions in a block is fine, but what if we wanted to include some control flow in our blocks at some point? Then everything could break.

8-bit and 16-bit atomic implementations

While RISC-V has atomic operations like amoadd, amoxor, amoswap (and more) to match x86-64’s lock add, lock xor, lock xchg (and others) by default it only supports 32-bit and 64-bit operations. An extension named Zabha adds 8-bit and 16-bit support, however no RISC-V hardware implements it right now. To emulate 8-bit and 16-bit atomics we need to use lr.w and sc.w and do some shifting and masking to perform the operation on an 8-bit or 16-bit value within the 32-bit word.

8-bit and 16-bit lock xchg support was added, as some games were using it, and failing to emulate this instruction atomically can lead to random deadlocks or data races.

Wine

Emulating the wine compatibility layer has caused us problems in the past, but after many bug fixes it has successfully run its first program, a simple hello_world.exe file.

For example, one of the problems was that we were using the host epoll_event struct to emulate the epoll syscalls like epoll_ctl or epoll_pwait. This is incorrect, however, as the epoll_event struct is packed in x86-64 but not packed in RISC-V for backwards compatibility reasons. This would cause issues with the wineserver communication and the application would get stuck.

Additionally, felix86 can now run a few simple Windows games through wine, which is quite the progress since last month:

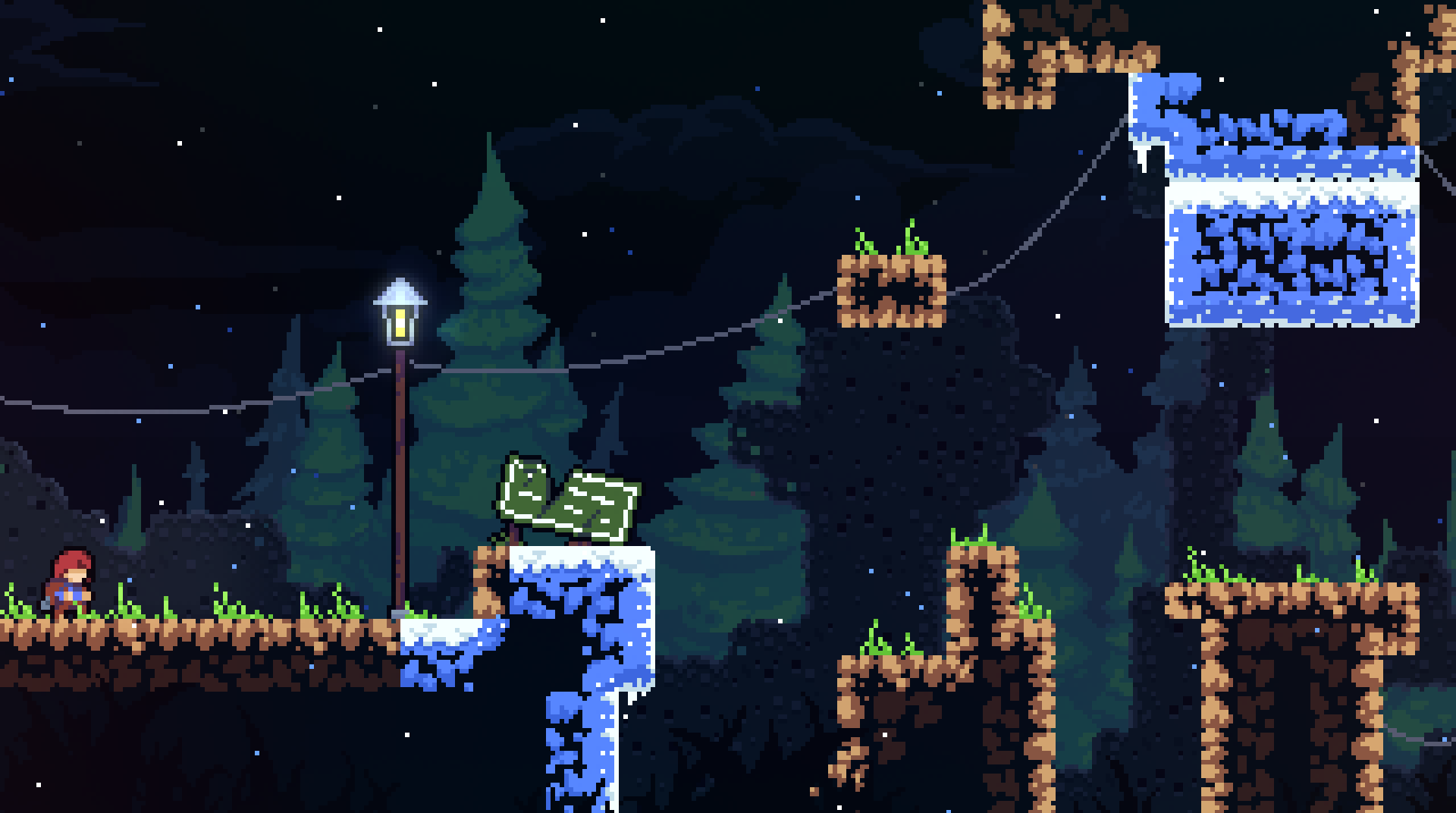

Windows 7 Solitaire now runs under felix86

Windows 7 Solitaire now runs under felix86

Better user experience

A few things have been added that will enhance user experience.

Config files

The emulator now has two ways of configuration:

- Using the

/home/$USER/.config/felix86/config.tomlfile that will be created after the first run - Using environment variables

Environment variables allow for quicker short-term configuration while editing the config file supports long-term configurations without polluting your global environment variables. You can print all the configurations by running felix86 --configs or by reading the config.inc file in the source code.

binfmt_misc support

binfmt_misc is a neat utility in the Linux kernel that allows executing file formats that wouldn’t be recognized otherwise. In our case, we want to detect x86 and x86-64 applications and try to run them under felix86. Registering an emulator for this purpose is quite easy. This means that, as long as the rootfs path is set and the emulator is installed, x86-64 and x86 executables can be executed without prepending the emulator path and the kernel will pass them to our emulator.

To register the emulator in binfmt_misc, use sudo felix86 -b. You can use the same command to unregister the emulator.

Kill all instances

Some applications, like wine, spawn a bunch of daemons that stick around even after the original application has been killed. A new argument is available in felix86, the -k or --kill-all which kills all active instances of felix86.

Moving towards 32-bit program support

With the latest changes, some 32-bit applications are showing signs of life! There’s no working 32-bit games at the moment, but we are inching closer.

New instructions

As we are moving towards supporting 32-bit programs, some previously irrelevant instructions become relevant again.

For example, the cmpxchg8b instruction, which was used in the pre-x86_64 era to perform a 64-bit atomic compare exchange, is needed for some 32-bit programs. Thankfully, this can be implemented with an lr.d/sc.d loop, unlike the cmpxchg16b which is currently impossible to emulate in an atomic way apart from some ugly workarounds. The Zacas extension is going to make proper cmpxchg16b emulation possible, but it’s not in the RVA23 profile so that may take a while. Regardless, felix86 will take advantage of the Zacas extension, if available.

New 32-bit syscalls

Along with instructions, new syscalls need to be supported for 32-bit programs. Unlike 64-bit programs, the syscalls here are more tricky to implement. Since pointers are 32 bits, there’s a mismatch with structs used in many host syscalls and marshalling needs to occur. For some syscalls like sendmsg this is trickier, as multiple structs need to be marshalled and lengths adjusted. There’s many syscalls that don’t occur in 64-bit mode and need to be emulated with modern syscalls.

MMX support

The MMX instructions are largely unused in modern programs because you have SSE instructions that can do the same things on larger registers. Still, modern programs sometimes use them.

For example, some versions of SDL2 have paths that have MMX support and integer support, but no SSE support, so at runtime the MMX path would be preferred. Since I procrastinated on implementing MMX, I disabled the feature in the emulated CPUID, only keeping it enabled during the initial ld.so checks, which assert that the ISA level is adequate to run the application.

There’s now MMX support, and 8 of the 15 remaining vector registers were statically allocated for the MM0-MM7 registers. In case you thought MMX registers are the 64-bit part of XMM registers (like I thought before starting this emulator), no, they are actually part of the ST0-ST7 x87 registers.

Because MMX and x87 FPU instructions operate on the same registers, the emms instruction is used before running any x87 instructions and after running any MMX instructions. This is great, because we have an easy switch point to flush our allocated MMX registers.

Most MMX instructions are implemented using the already existing SSE handlers, while some like punpckh have differences due to the smaller register size, so they were handled with a little more care.

That was it for the May post! See you in a month or two!

There’s still a lot of work to be done – don’t hesitate to join us!

If you find this project interesting, please star the repository.